Women Talking About Women Talking

A field report from the Education For Women's Liberation conference in London

Last weekend, I was one of many women who travelled to London to attend the Education for Women’s Liberation conference. Cohosted by Woman’s Place UK and University College London’s Women’s Liberation group, the event page set out the theme for the day as such:

Focusing on education in feminism and women’s lives, the conference will address interconnected themes including: women’s voices in education; sexual harassment in schools and universities; the history of women’s access to education in local and global contexts; the ways in which women’s entrance into education and research has changed workplaces and academic disciplines; the impact of gendered stereotypes in educational spaces, and sex and relationship education in schools.

To be honest, nothing about this description sounded exceptionally exciting at first blush. Bog-standard feminist fare, this would have seemed to me, when I finished my Women & Gender Studies degree nearly sixteen years ago. Back when you could use the word ‘women’ and no one batted an eye, because everyone knew exactly what that word meant, and had always meant (whereas almost no one I spoke to outside of my major seemed to have even heard of ‘gender’). But somehow, speaking about the female experience has been shunted out of the centre of feminism since then. It now tends to get labeled as ‘radical’. And therefore, something to get excited about after all.

Which meant two things. First, that the conference was sold out; all 900 tickets had been snapped up. And second, that when I rocked up at 9am with my own ticket in hand, I had to get past protesters. Of both sexes - and of various genders, I’m sure. There weren’t many of them, and they weren’t up to very much when I walked past (though apparently things did kick off more later in the day), so I didn’t pay them too much heed. But the overall impression I got at that early hour was of young-ish women. Women protesting against the right of women to meet and speak to each other about women’s issues and rights. Who could apparently only conceive of an organisation that would put together all-female panels on women and education as a ‘hate group’, and therefore stood outside chanting “Shame!” at me as I walked past, and at the university for allowing such an event to take place on their campus.

On that very same day, and every other day I traveled around that massive metropolis, I saw posters all over the underground for the film Women Talking. It’s based on a novel that was based on actual events. Where a group of men in a Mennonite community decided it would be a swell idea to source animal anaesthetic from a vet so they could knock out and rape over 100 women in their colony. I mean, it says ‘women’, but amongst those brutalised were girls as young as three. Three.

And indeed, the trailer for the film is narrated by a little girl’s voice. As it opens, she says, “Where I come from, where your mother comes from, we didn’t talk about our bodies.” As she says this, we see Rooney Mara’s character waking up to discover bruises across her thighs that look far, far more like the markings of a car crash than anything I’ve ever woken up to in the twenty years since losing my virginity. The rest of the trailer shows the women of the colony discussing whether they should leave their home, or stay and fight the men.

So. On the one hand, a film about women talking. That is explicitly called Women Talking. Featuring almost nothing but women talking. About the fears and responsibilities and vulnerabilities and choices that are distinct to their fate of being female. Exploring their options together, with minimal input from men. In the context of a Hollywood production, such activities are deemed worthy of a premium marketing push, and widespread acclaim.

And on the other hand, a real life gathering of women talking. Women who work as writers, lawyers, teachers, health workers, researchers, politicians, organisers, artists, and in all manner of other occupations. Talking. About our fears and responsibilities and vulnerabilities and choices as females. Exploring our options together, with minimal input from men. In the context of a university campus, such activities are deemed ‘hate speech’ by some locals, and require a small security detail to make sure women aren’t accosted as we come through the doors.

It seems a strange juxtaposition to me.

Women. Using words. Clearly, as a woman writing, this is something I care about very much. But it’s much more than vocational. I’ve recently come to realise it has probably been the preeminent preoccupation of my life. I tend to think of words as what I am best at, but, in truth, I struggle with them terribly. When there’s something I really care about expressing, my jaw clenches, my stomach turns into a ball of acid, and I shake so much I can’t sit still. My whole body conspires to steal my fingers and mouth away from my mind, and leave me mute. Classic signs of a fight-or-flight system hijacking.

I used to assume this was pretty normal. And I think, unfortunately, some version of it is. But lately I’ve been wondering whether I’m actually a particularly reactive case. I grew up in a household where having a ‘smart mouth’ was punished, sometimes quite physically, and sometimes with words hurled so violently, their impact felt physical. Both hurt, and both were terrifying. Again, I don’t think there’s anything that unusual about such an upbringing, and know many homes are much more oppressive. But I find it unlikely that it wouldn’t be at the root of whatever has trained my body to be so very fearful of upsetting anyone by speaking. And wonder how much other people - particularly women - struggle against this same conditioning.

When I first escaped to university, and discovered Women’s Studies, and feminism, I was captivated, and elated. I thought I had found the tools that would save me, and other young women, and possibly humanity altogether: words. Like patriarchy, and misogyny, and coercion. Like consumerism, and objectification. Like structural, and complicit. Like vindication, and liberation. And praxis. Words that could spell out why the world was so scary and sordid and astonishingly unfair, and words that could sketch out plans for us to make it better.

However, I did not foresee that these very words would become feminism’s great quagmire. I mean, I knew women could be silenced by preventing us from using our words - by barring us from places of learning and discourse, or by physically strangling our words as we tried to push them out of our throats. What I didn’t realise was how silencing could be achieved just by stealing our words away from us; by gutting them of meaning. That we would get to a place where a preeminent medical journal would think it was better to refer to my sex as “bodies with vaginas” rather than ‘women’. That just as I became brave enough to take on the ultimate transformation and responsibility of becoming a mother, certain activists and politicians would try to steal that brutally hard-won and most meaningful title from myself and mothers like me, and try replacing it with the much diminished term ‘birthing parent’ instead. That the unrelenting marketing of cosmetic products and procedures that my professors had taught me to describe as ‘exploitation’ would be rebranded and celebrated as ‘empowerment’. That the term ‘adult human female’ would, for many, become synonymous with ‘terf’, which would in turn become synonymous with ‘bigot’. And that ‘feminist’ and ‘patriarchy’ would each get bandied about so wantonly as to almost become gibberish. And so on, and so on. So that the so-called feminism of the so-called mainstream would become the stuff of Orwellian Newspeak, stopping women’s gains of the last century in their tracks, and sometimes shoving them backwards. Because how can you advocate for a thing that you can’t properly speak about?

And it was this perversion of the language, this stealing of words, this silencing, that lay at the heart of the conference. Though formally about education, the thing that the speakers and panels and attendees all kept returning to was words. They spoke of many other important things, too, like civic education, public policy, incarceration, assault, safeguarding, and class. But over and over again, what all these disparate issues kept coming back to was the struggle around language. That was the real matter at hand; a reclaiming of what women are allowed to think and research and say. The necessity of having words to accurately describe our lives and bodies, and thus value and understand and protect them. Including, crucially, the word ‘No.’ From the opening remarks of barrister Akua Reindorf, stating that debate is how bad ideas are “exposed to the disinfectant of sunlight,” and that, “There is no inclusion where people are silenced.” To the closing remarks of organiser Ali Ceesay, calling out the “demonisation of girls who say ‘no’ to misogyny,” and insisting that, “talking about our lives will never be an act of hate.”

And in between the opening and closing it was the same; words, and what they mean, and why it matters how we use them. The morning offered an option of five panels. It was a hard choice, but I ended up going to the panel on women’s voices in education - in part because it was going to be chaired by Kathleen Stock. I only found out after I’d taken my seat that she was not able to be there that day after all, and that was a disappointment, to be sure. But the panel ended up being great all the same. The highlight being, in my eyes, Professor Judith Suissa, who spoke with a combination of intelligence, clarity, and vehemence that I can only marvel at and aspire to. “Telling us not to speak of and name our bodies,” she concluded, “is of a piece with trying to control our bodies.” Which should hardly need saying. And yet, it does. In real life just as much as in movie trailers.

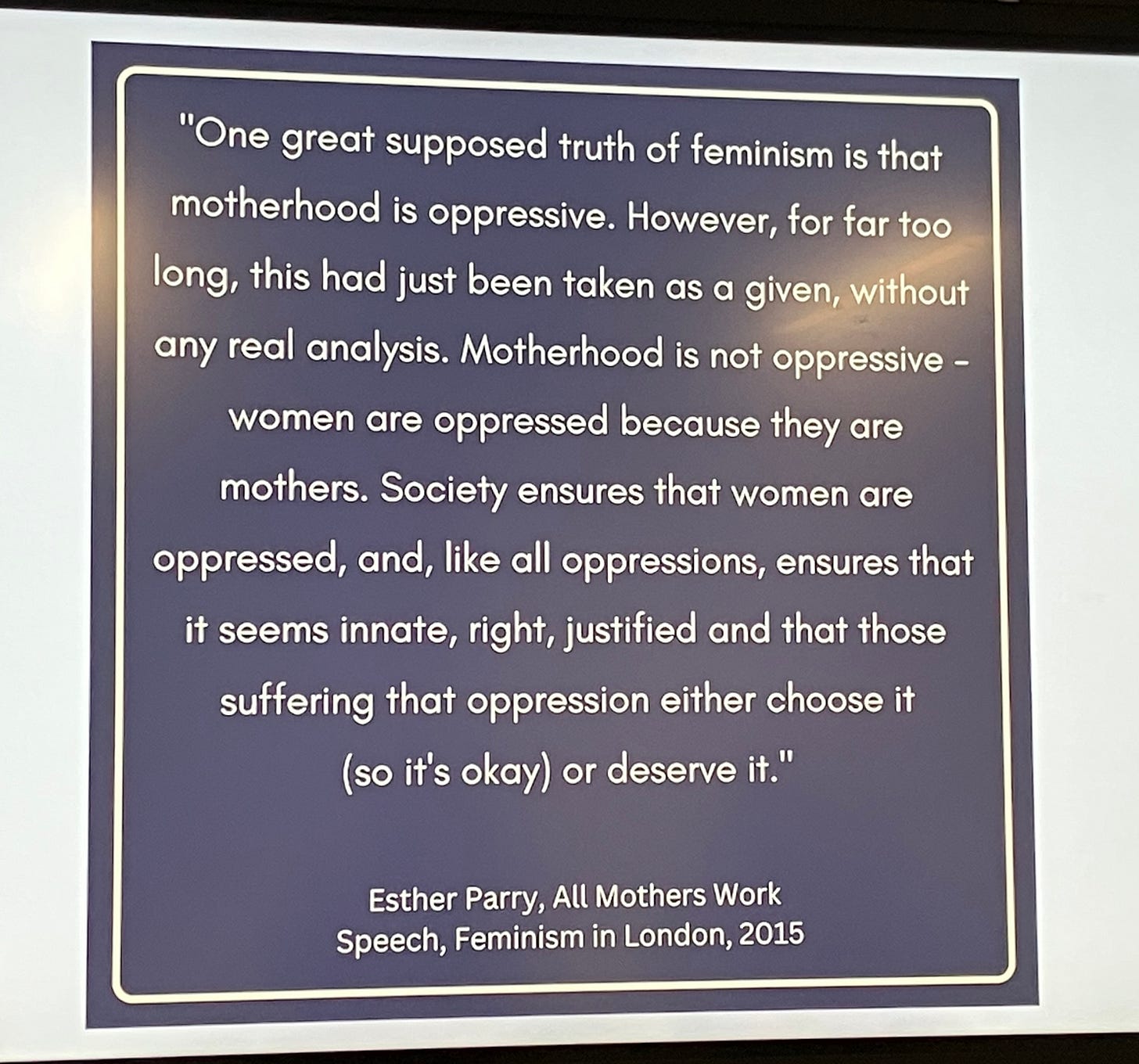

In the afternoon, we could choose just one of the twenty-one workshops. That took some fierce agonising, but in the end I decided I really ought to go to the one run by a group called With Woman, about language and maternity. Because that is obviously very much in the realm of what I’m trying to work on with this Substack. The workshop was interesting, but a bit wide-ranging for such a short time slot. However, it did lead me to a couple of exciting resources. The first is a group called All Mothers Work, which no longer seems to be active, but for a while produced glorious statements such as this:

The other was something the presenters kept calling ‘The Paper'. ‘THE Paper’. Which I have since downloaded, and read, and highlighted. And will be referring to a lot going forward, I am sure, and I may even do a whole post on it. Because it deals very thoroughly with the recent push to de-sex the language used in reproductive, maternity, and newborn care. And how, in an effort to make their language more ‘inclusive’, providers are actually making it less clear, less accurate, and less helpful - and indeed, making it dehumanising, and sometimes dangerous to the point of life-threatening. For the children involved, as well as the mothers.

The women who organised the conference, and many in attendance, tended towards the purple, white, and green colour scheme of the Suffragettes. The programmes and lanyards we received were in these colours, and many women were wearing scarves in this combination. I have no such scarf, but I do own a small book called Suffragette Manifestos. Its cover proclaims:

Which sounds nice and punchy, but is actually a chopping up of something Emmeline Pankhurst said in a speech she gave at the Royal Albert Hall in 1908, the transcript of which is contained in said small book:

“They said ‘You will never rouse women’. Well, we have done what they thought, and what they hoped impossible - we women are roused. Perhaps it is difficult to rouse women, and they are longsuffering and patient, now that we are roused, we will never be quiet again.”

I wonder if Ms. Pankhurst really believed that patience was what made women hard to rouse. I, for one, have never been known for my patience. Nor have I ever looked into the swirling mass of feelings inside me and thought, Ah, that’s what’s bothering me. I’m too patient today. Nope. I reckon that if women then were hard to rouse, it would have been for the same reasons as today. Most of which boil down to one thing: fear. Fear of being seen as selfish, or unkind, or on the wrong side. Fear of being kicked out of social groups. Of losing our jobs, and being unable to support ourselves and our loved ones. Of threats to our children. Of being attacked. Arrested. Ostracised. Silenced.

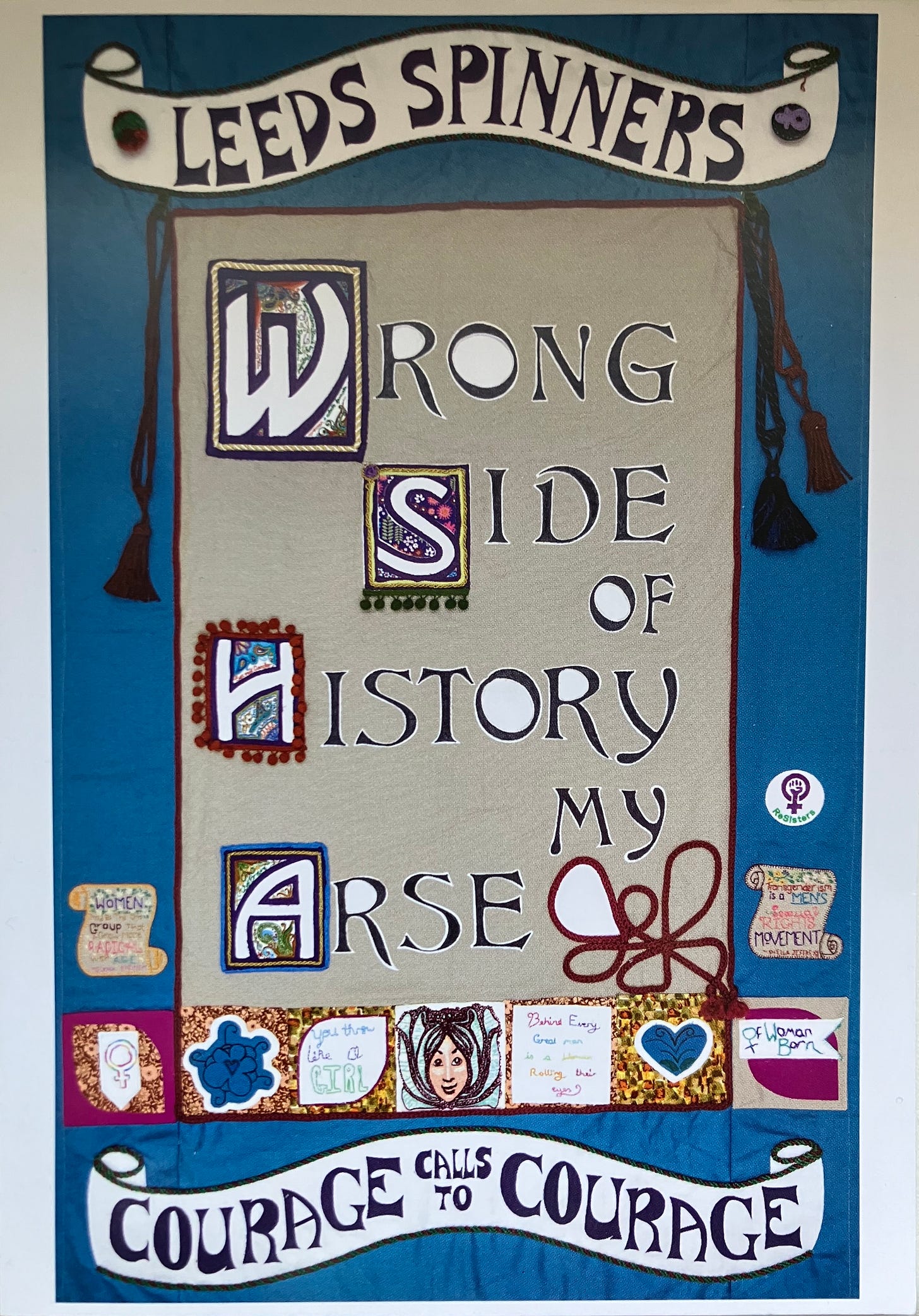

Most of the above did happen, in varying combinations, to the women speaking at the conference. Except the silencing part. Silencing was the intended effect of all the other crap thrown at them. But they were not silenced. And instead, they received thunderous applause from the better part of a thousand women last Saturday. Over and over and over again.

Truly, the real benefit of going to the conference was just to hear these fantastically unsilencable women speak about how bizarre (or as Helen Joyce perfectly put it, “incredibly stupid”) this situation is that we find ourselves in. And for those of us who are less assuredly vocal to have the chance to talk amongst ourselves, too. Judging by my own experience, the handful of women I had good conversations with, the many other women who asked questions in the panels and workshops, and the wave after wave of applause across the main hall, there was a huge amount of catharsis taking place, along with a replenishing of courage. Which I needed as much as anyone. And I felt that the lockdown years, and the disconnection that came with them, really are behind us now, at last. And that a new phase, inviting new words and interactions and choices, lies ahead.

If you’re interested in hearing more about the conference, you can find quite a lot of other women’s coverage of the day by using #Ed4WomensLib. Or if you were there yourself, and want to say hi, by all means - let’s talk.

Thank you! What an amazing gathering of power that was.

I do have one question, were the protesters confusing the title of the conference and the movie? If not, what was the issue they were standing for?

I was there! It was wonderful. Wish I’d known you were there too I’d have loved to meet you - next time!