This past summer, I went to a magic mushroom retreat. I went, as one does, for many reasons, but for one in particular. The prior winter, I had finished writing my first novel. Which, for me, was a big deal. The only thing I have ever really wanted to be, since I was about nine, is a writer. Yet for more years than need counting, I could not admit that that was clearly and exclusively the vocation that called to me. It had taken the good fortune of marrying my favourite writer to change that. A fellow with world-class teaching skills whose conviction in the importance of stories, confidence in my capability, and feedback, offered unflappable guidance in the face of my many fears and freak-outs.

And after a few years of living with and like a writer, I found that I had actually become a writer. It was no longer something I wished to be – it was simply what I did. All the time. In virtually every moment available to me. Which, once we had a baby, and the pandemic hit, were moments I really had to fight for. And I did. And in those dark, depleting winter months of the Berlin COVID lockdowns, I put every scrap of energy I could spare into finishing my novel. And the results, I believe, are really great. Not great as in ‘Great Literature’ (which is not something I aspire to write), but great in the sense that it’s a fun read that’s about something. It’s wholly it’s own odd little thing, and I love it. And I say that as someone who can easily find fault with everything they do. This, for all its weirdness, I fully stand by.

But there came a point, after several months of nothing but rejection from literary agents, where I started to slide into a depression. Here I had spent years learning how to write (and not doing other actually paying work), had buckled down and actually finished a manuscript, and my labour of love still wasn’t good enough, it seemed, for anyone I shared it with. Was it time to give up, and do something else? But what? I’d done loads of other ‘real’ jobs, and had been kind of crap at most of them. Writing was the only work I felt unequivocally good at, and the only work I wholeheartedly loved doing. It was the only work that mattered to me. But being able to take care of myself and my family mattered at least as much, if not more. So what was I supposed to do?

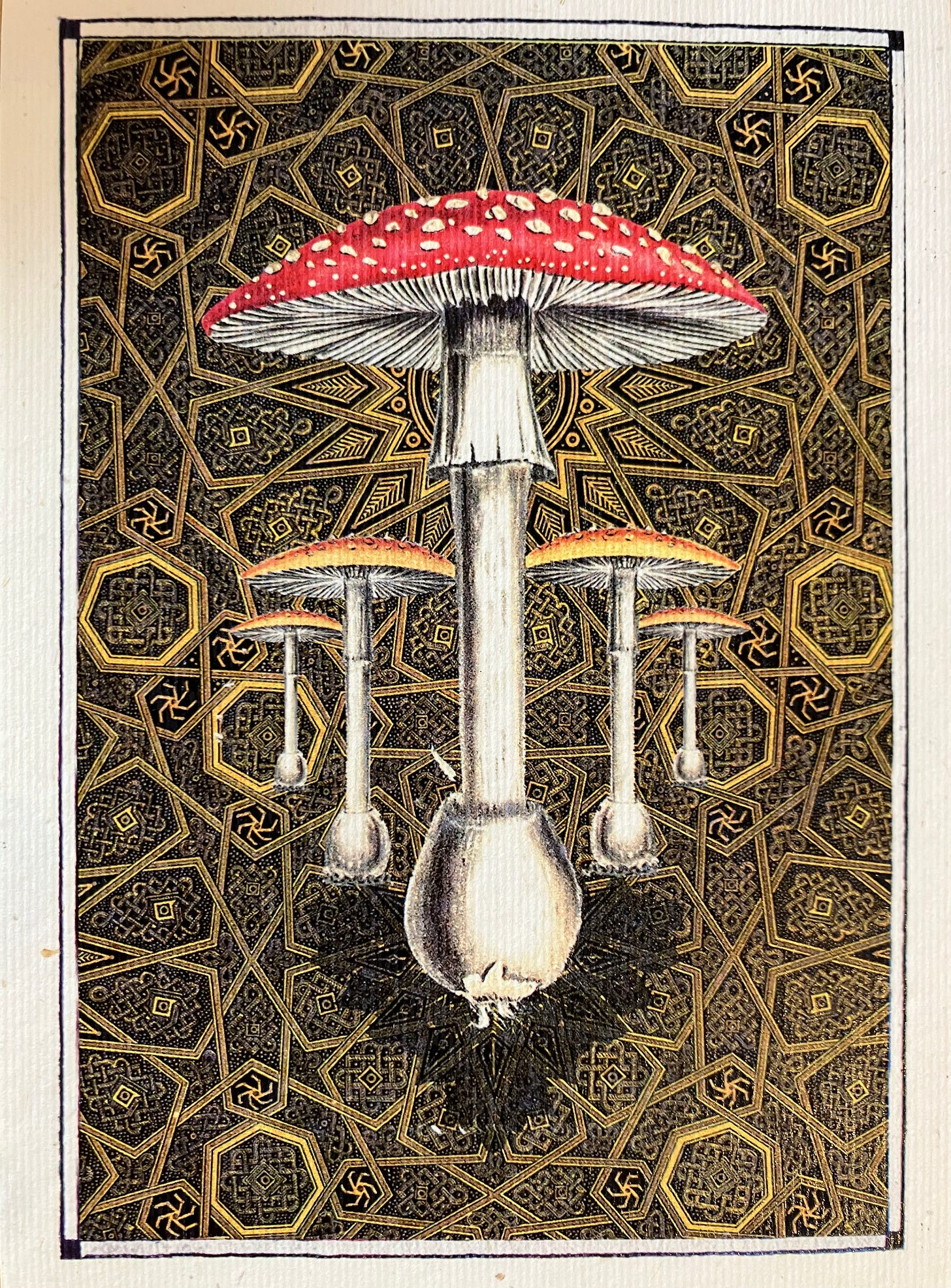

Around this time, I saw yet another article in the news about psilocybin and its use in treating depression and other mental health issues. So I took a train out to some lovely Dutch farmland, entered a wooden temple with a colourful geodesic roof, sat down by the immense fireplace at its heart, and got just unspeakably, gobsmackingly high. For two nights in a row.

The first night, I wept. It wasn’t sorrow, or joy, or any one emotion I was crying with; it was emotion in its totality that came pouring out of me, in a shower of tears and snot. I felt physically pinned down to the ground by the flood of it, and the stray drops escaping and spattering across the wooden floorboards looked like blood in the firelight. One of the men working there periodically approached to offer paper towels. Otherwise, I was left to get through it. And when I peered around at the others in the group that were visible from my low vantage point, they seemed to be having a similarly heavy time of it, too.

At some point, I was able to sit up, and think. And one of the things I thought about most was Ursula Le Guin. In the brief time I lived in Oregon, I saw her speak twice. People would ask her all these grand questions about writing and creativity, as though she was some anointed figure of a mystical order. And she would give them nothing in return but the very bluntest of blunt grandma answers, which all boiled down to basically one thing: Ya gotta just do the damn work. Of course, what made her famous is that her ability to do the work was off the charts; her capacity for world-building was absolutely unhinged. She laid down whole vocabularies and ethnographies and terrains like she was simply recounting a film she caught on tv the night before.

The unique collision of unblinking pragmatism and epic imagination Ursula embodied made me admire her from when I first encountered her. But what made her my hero is something we didn’t share in the years she was alive, because I only got pregnant six months after she died; she was a mother. Across the years she penned the many works that most made her a legend, she was up to her elbows in motherhood with three small children. I had just completed one book with one baby to look after, and that had felt herculean. How on Earth had she done it?

So I sat by that temple fire, thinking about this great mother-writer, and wishing I could talk to her. Here I’d had the chance to cross paths with her, but had neither books nor babies of my own then, and could not foresee that she was to become my great role model. And now it was too late. There was no hope of getting to speak with her. Of sharing a laugh. Of saying thank you. Because she was gone. And neither she nor I particularly believed in the kind of afterlife where she would be waiting around in the ether for me to tell her.

Well, I could tell her anyhow. I could sit with it, the gratitude, and just love her anyhow. Even if I was the only one who knew about it. And that would have to be enough. I mean, clearly, it wasn’t truly enough; it wasn’t anything like what I wished. But it was what it was. It was, and it was powerful. And I was, though a little sad, ultimately very glad of it.

Making life, making worlds. Sitting there, staring into the fire and the fabric of time and space, it seemed unquestionably clear that they were the only truly meaningful forms of work to be done in this life, and quite likely the only reason for the universe to bother existing. And, like Ursula, I was labouring away in those two most generative fields. There was a unique human being, and a unique little world, where neither had been before. It was a perpetual and wonderful surprise to me that they really truly existed; and they did so only because I had dearly desired that they should, and worked like hell to actualise them. Even riddled with psilocybin, I had no illusion I’d ever become as prolific as Ursula. But I knew I was doing the best I could. And even though that best often didn’t feel like enough, it was as much as I had, and I was giving it. And I could be glad about that, too.

The second night, I didn’t want to spend the whole ceremony glued to the floor again, so as soon as I felt myself coming up, I snuck out of the temple to go watch the sky. I gazed at the clouds (which, as you might guess, looked amazing), and let my thoughts roll through with them. After about an hour, I had a clear, perfect breakthrough on a project that had been stymying me for years. I pulled a pen and small notebook from the breast pocket of my ratty old army jacket, and as I took notes, the blue ink seemed to emanate from my hand in rainbows. The last words I wrote, carefully, were: Mama Dentata. There it was. I knew exactly what I needed to do when I got home.

Satisfied with this sky session, I crept back to the ceremony, and was happy to find the others were also in a more jovial mood than the night before. Rather than being locked into our individual inner dramas, there was a great deal of group banter, laughter, and even singing. We were tumbling about together like children on the world’s weirdest sleepover. Towards the end of the night, when we were starting to come down a little – but still very, very high – the ceremony leader told us that if there was anything we felt we still hadn’t dealt with, we should tell it to the fire, rather than carrying it back out into our lives.

Did I have anything? What had I carried with me to this place, that felt heavy?

“I love you, Brian,” I found myself blurting out. And by Brian, I meant the Eno one. The novel I had written was inspired by his album, Another Green World. And every time I thought about this fellow and his work, it was with love. Indeed, I’d spent much of the last few years writing in a state of sustained hallucination fuelled by it, so my love of his work was all tangled up in my love for my work. What a mess.

And once I admitted one love I was embarrassed of, I found I could not stop. I named every single person I could think of that I had any affection for. Not just the family and friends I actively loved in the present, who were easy and joyful to think of. But all manner of characters haunting my past; estranged family members, childhood friends, college roommates, ex-boyfriends, and dead pets. Entwined with that rambling list was another; authors, musicians, performers, and podcast hosts. One was a list of people who were no longer physically present in my life, and the other was of people who never had been. But they had shaped it all the same.

As the music and conversations and hallucinations carried along merrily around me, I kept finding my mouth opening to let another name fall out, and another. Anyone I could think of, who I had even one memory of that made me smile, joined the list. This went on, I believe, for about two hours. And I realised how many people (and other creatures) there were to name, and how much affection I carried. But I also realised I had been putting a lot of energy into censoring the affinity I felt for them. Why?

Because I didn’t want to feel it. Or didn’t think I ought to feel it. By why was that?

Because it hurts to have love for people who have hurt you. And it can also hurt to have love for people who have absolutely no idea you exist. Both feel foolish, in very different ways. Any love that is not reciprocated cannot help but cause at least a little heartache, and sometimes results in real violence and ruin. And so we can feel, accurately, that love is not a safe place to dwell. But the love is there all the same. I really did, in different ways and degrees, have some amount of love for every person who came to mind. Even if it was just a spark. And even if they’d behaved appallingly. And yes, I know, I was very high, but the psilocybin didn’t invent any feelings, it just suppressed my ability to lie about them. These people had played a significant role in my life, and how I saw the world. Sometimes for just a little while. Sometimes across decades. Whatever else they had or hadn’t done, they had each done something to make the world more funny, beautiful, arousing, nourishing, or compelling… and by extension, more worth living in. And so it made me smile to think of each one of them, and things they had said or done or made. Whether or not any of these people knew about it, I knew. I carried their actions with me, like gifts; which of course they were. I had gratitude. And love. And those were feelings, but also facts. And rather than fighting them (which was futile), and feeling ashamed of them (which was draining), I could try to accept their presence, and feel less lonely in the world, and be glad about it.

In my years of researching my novel, I heard Brian Eno say repeatedly that art is “everything that you don’t have to do.” By this he means for sheer survival; we have to communicate, but don’t have to sing, for example. But he’s wrong, of course, because we do have to do these things. It’s how we show our love. Which we have to do. Humans are often described as social creatures, but that implies that we’re animals that just need to, I don’t know, go sit in the pub once in a while. No. ‘Social’ is too weak a word. It would be more accurate to call us, as David Byrne has, Creatures of Love. From the moment we arrive in this life, we need to engage with the world in a loving, enthusiastic way, and have it engage thus with us back. Otherwise, we don’t really survive; we die deaths of despair, at varying speeds. We fall apart. And so does the world around us for that matter. Mr. Eno would be more correct to say art is everything done out of the impulse to love and the enthusiasm it generates, rather than coerced toil and begrudging obligation. That is what art is. An act of love, and an expression of human desire. Which is what life is meant to be as well. Which I guess is why the boundaries between ‘art’ and ‘life’ so often blur together. They certainly do for me, anyhow.

The mushroom weekend clarified that my dual roles of mother and writer are manifestations of the same impulse to create and to love. Accepting and delighting in my son as he is has come easily for me, and in the process of integrating my mushroom trips, I have been able to extend that mindset to my other creations. Accepting and delighting in all the other manifestations of my impulse to love is, not surprisingly, a lot harder. But the mushrooms showed me how much energy I was wasting on trying to push them away. So I am trying. At least I am committed to being honest about them now. As you can see.

I am still left with the problem of how to be able to afford to live while I do all this work, which I find so valuable, but which the formal economy does not. But the mushrooms gave me the name and intention for Mama Dentata. Perhaps, with luck and diligence, this Substack-ing will lead to something, in one way or another. We shall see. In the meantime, I do it as a labour of love. Because that’s what I’m here for.

p.s. I love mushroom stories. If you have any anecdotes or questions you want to share in the comments, please do. If you’d rather not have that chat in public, that’s fair enough; feel free to send me a message directly instead.

p.p.s. I kept thinking of so many songs as I was writing this. So I’m working on a playlist for this post. I’m looking for songs that fit the theme of us being creatures of love, or have some sense of cosmic/ transcendent love, or love as life force. Although, I would also consider songs that are just about being super high. : ) Suggestions?

Love! Great, now Im crying... I feel like I just went on a beautiful love fest adventure, the best kind. Im feeling all awkward to say it, but it's true, (and a really cool European mushroom trip isn't in my budget right now) so what the hell... I love you Solana!

Maybe that song "What the world needs now is love, sweet love" is apropos?